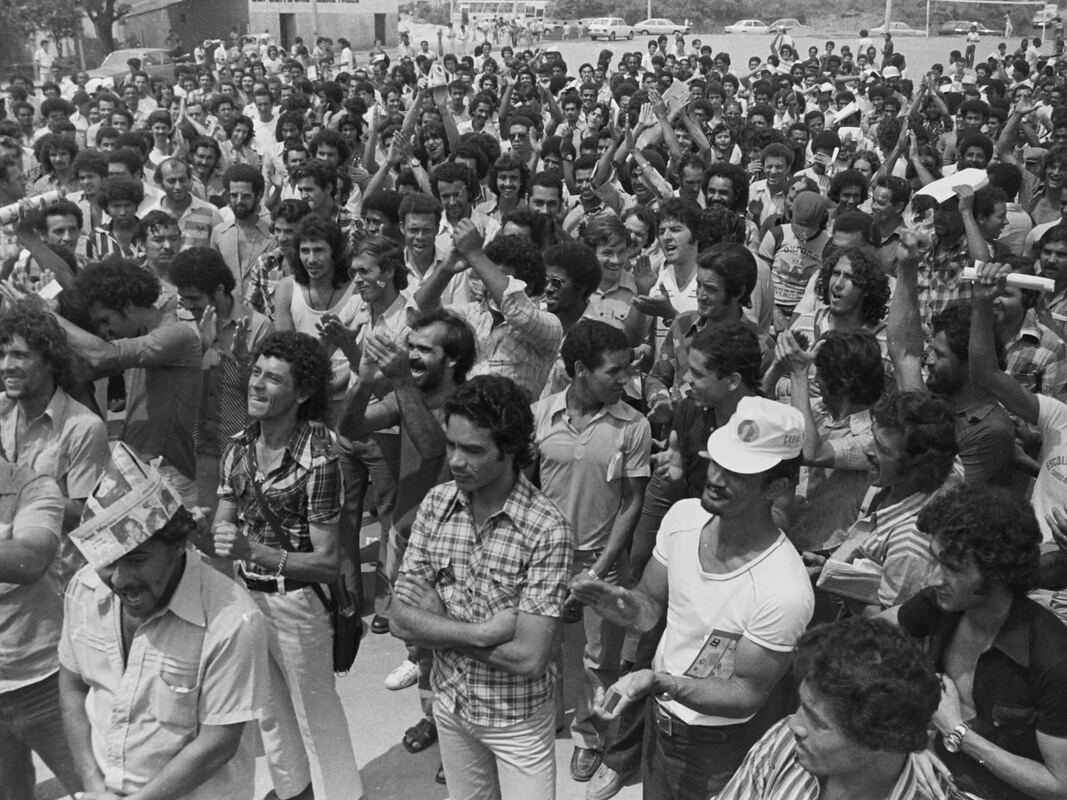

(by Janaina Cesar, Pedro Grossi, Alessia Cerantola, Leandro Demori. The Intercept) In October 1978 Fiat Brazil’s workers were on the verge of their first strike. The Italian carmaker’s factory in South America would go on to become its most successful: Today, more Fiats are produced in Brazil than in any country besides Italy, and Fiats are the third most popular car in Brazil. But 40 years ago, as Fiat was growing into its Brazilian operation, turmoil was on the horizon. At the Fiat factory in the Brazilian state of Minas Gerais, workers, fearing repression, had been organizing in secret. The military, which had taken power in a 1964 coup d’état, sometimes violently opposed labor organizing. Yet the Brazilian and Italian Fiat executives couldn’t ignore the palpable energy on the factory floor in Betim, the city where the Fiat plant had opened only two years earlier. Six days before work would eventually come to a halt, Airton Reis de Carvalho, the precinct chief with the local police department, sent a letter to the military. A Fiat worker had been spending hours in front of the police station, trying to locate and free a jailed colleague who was viewed as indispensable to the push for a strike. “There really were Fiat employees who were detained,” Reis explained in his letter. “All of the measures taken by our precinct in this case were in keeping with our agreement with Colonel Joffre, of the Fiat Automotive’s security department.” Reis was referencing Joffre Mario Klein, an army reserve colonel who had joined Fiat’s Brazilian operation in its early days — and who would be at the center of the company’s machinations against its own workers. Under Klein’s careful watch, the Italian carmaker had been spying on Brazilian workers in collaboration with the military dictatorship. Klein’s role in keeping Brazilian workers in check for Fiat, along with a long list of repressive moves by the company, are coming to light after a yearlong investigation by The Intercept Brasil, which tracked down documents from archives in Italy and Brazil and interviewed ex-workers at Fiat, former union leaders, and prosecutors in both countries. The repression of labor at Fiat Brazil came thanks to coordination between the security apparatuses of the Brazilian government and a massive clandestine espionage network operated within the company itself, according to documents at the Minas Gerais public archive. Headquartered in the auto plant and commanded by Klein, Fiat’s internal espionage division employed dozens of civilian and military spies who investigated the lives of workers and helped the abusive dictatorship put agitating workers behind bars. While Fiat’s network of spies operated far beyond the factory walls, closely tracking workers’ activities, the company also invited government repression onto its premises, according to documents from the Office for General Security, a now-defunct division of the Minas Gerais state police. The Brazilian Department of Political and Social Order, a police force known by its Portuguese initials, DOPS, operated freely among Fiat workers. DOPS was infamous for frequently taking the lead in brutal government campaigns of repression against social and political activity, and had employed torture and murder among its tactics since the 1950s. These were the dark forces infiltrating union meetings with the blessing of Fiat Brazil’s own security apparatus. Fiat’s spying operation in Brazil had a parallel back home in Italy. Fiat engaged in the same pattern of espionage in Italy during the “Years of Lead,” a time of Italian political and social turmoil in the that ran from the late 1960s through the late 1980s, according to a second batch of documents from Fiat’s official archives in Turin, Italy, as well as documents from the federal courthouse in Naples, Italy. The Italian spying operation was exposed in the 1970s, when the prosecutor Raffaele Guariniello conducted an investigation and found that Fiat had developed a system of pervasive espionage. A former secret service agent headed up the internal spy ring, and police, judges, and ex-military men were all implicated. The spies compiled hundreds of thousands of files with information about workers’ private lives, including intimate details. The information would prove useful for Fiat in identifying union leaders and ferreting out strike plans. Years after the investigation was complete, the case finally went to court, and some public officials and Fiat executives were convicted. While many of the details have come to public light, however, the history of the Italian spy ring is likely to remain a patchwork: A substantial portion of the evidentiary files from the case have disappeared. In April 2018, in response to an initial inquiry about this story, Fiat Brazil said, “We consulted several sources in the company, but there is really no memory of such events.” In February of this year, Fiat Brazil offered the same comment in response to a detailed inquiry and declined to make company officials available for an interview. Fiat’s Italian headquarters referred The Intercept to the Brazilians’ statement and added, “Regarding the issues concerning Italy, we have no comments to make, because they are well-known things that have been reported in newspapers on many occasions in recent decades and on which books have also been written.”

0 Comments

|

Archives

August 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed