|

By by Stevan Dojčinović, Pavla Holcová, and Alessia Cerantola for Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP)

Mileta Miljanić, a Bosnian-born U.S. citizen, is a wanted man in Italy and faces arrest if he so much as changes planes there. In New York, a 2003 federal indictment of Miljanić remains inexplicably open, with no apparent move to take him to court. So it’s easy to find the leader of “Group America,” a brutal cocaine trafficking network that operates on at least four continents and is said to be responsible for a dozen murders. He keeps an apartment in a neat townhouse in the Ridgewood neighborhood of Queens, New York. His surname is on his doorbell. Sometimes he even appears on television.

0 Comments

The Sin Tax: How the Tobacco Industry’s Heated-Tobacco Health Offensive is Sapping State Revenues12/8/2020 In July this year, senators in Rome received a letter from the local head of tobacco company Philip Morris, containing what he promised was “very important news for Italy.” The letter highlighted the U.S. Food and Drug in Administration’s (FDA) decision that month to allow Philip Morris International (PMI) to market its flagship heated tobacco device, IQOS, as exposing users to fewer harmful substances than traditional cigarettes. “The FDA clearance confirms that IQOS, although not without risk, is a fundamentally different product from cigarettes,” wrote the president of Philip Morris Italy, Marco Hannappel.ui per modificare.

By Alessia Cerantola for OCCRP

Japan’s government has been criticized for its slow and inadequate response to the outbreak of the coronavirus. Japanese organized crime, meanwhile, has moved to take advantage of the crisis. The pandemic has become a new battlefield for the country’s criminal gangs, with older “yakuza” groups trying to restore their reputations through public works while newer gangs vie for profits from selling medical supplies. The yakuza, which means “good for nothing” in Japanese, have reportedly been handing out free supplies to desperate shoppers and even offered to clean up a quarantined cruise liner in a bid to curry favor. “In this way [the] yakuza, who have been perceived negatively in recent years, hoped to become more socially accepted,” said Garyo Okita, a journalist and expert on the yakuza. By Alessia Cerantola for OCCRP

When senior Rome customs official Concetta Anna Di Pietro received a call from her colleague in Milan telling her that British American Tobacco had put out unauthorized signs advertising its cigarette prices as “locked in” at current rates — unlike their competitors’ –— she flew into a rage. Di Pietro’s anger was captured in wiretaps made by police, who arrested her in December 2019 over allegations that she colluded with Philip Morris, the main rival of British American Tobacco (BAT) in Italy. She was accused of leaking confidential information and delaying announcements on changes in tax rates to give Philip Morris an edge in making pricing decisions. By Lorenzo Bagnoli and Alessia Cerantola for The Atlantic

MILAN—The annual meeting of the League appears at first to be a casual affair: Supporters of the far-right Italian party gather in Pontida, a small town north of Milan, milling around barbecues, drinking beer, chatting, and singing. It looks more like a festival than a political conference. The politicians who attend—and all senior League officials do—are easily approachable and willing to talk (to activists, if not journalists). For the League’s members, it is like a pagan Christmas—those who were naughty over the course of the year are relegated to the background, while those who were nice are feted onstage, crowds chanting their name as they deliver a speech, each speaker more important than the last. The final address always goes to one man: Matteo Salvini, the party’s leader since 2013. And this year he is honoring Luca Toccalini. Just 29, Toccalini has served in Italy’s Parliament for more than a year but has been coming to these meetings since he was a teenager. Back then, his ambitions were decidedly more humble: aiming to be the cashier of a small restaurant in his hometown, where his two best friends would work as cooks. He became involved with the League (then a regional party called the Northern League) only after he was handed a flyer on the street, and the relationship soon deepened. At this latest annual conference, Salvini would name him national coordinator for the party’s youth department. It is an influential post, responsible for organizing and campaigning. Yet the connection between the two men also carries a powerful symbolism: If Salvini, Italy’s former interior minister and deputy prime minister, is at the forefront of the far right’s current ascendance in Europe—its most famous face, according to fellow populists—then Toccalini points to the movement’s future. He and others like him represent a growing movement of young activists in Italy and across Europe who identify not as the far right, or even as nationalists, but as identitarians, concerned primarily with the preservation of what they believe to be their societies’ long-held identities. They promote Christian values against what they claim is the forced Islamization of Europe; heterosexual families rather than gay marriage or even civil partnerships; and local traditions as opposed to mass migration. Across the continent, from Eastern Europe to France and from Greece to Scandinavia, these identitarians have loudly proclaimed their presence, perhaps nowhere more so than in Italy, and perhaps none more so than Toccalini himself. “I was born in the League,” Toccalini told us. “I will die in the League.” By Alessia Cerantola for The BBC World Service. In Japan, more and more children are refusing to go to school, a phenomenon called "futoko". As the numbers keep rising, people are asking if it's a reflection of the school system, rather than a problem with the pupils themselves. Ten-year-old Yuta Ito waited until the annual Golden Week holiday last spring to tell his parents how he was feeling - on a family day out he confessed that he no longer wanted to go to school. For months he had been attending his primary school with great reluctance, often refusing to go at all. He was being bullied and kept fighting with his classmates. His parents then had three choices: get Yuta to attend school counselling in the hope things would improve, home-school him, or send him to a free school. They chose the last option. Now Yuta spends his school days doing whatever he wants - and he's much happier. Yuta is one of Japan's many futoko, defined by Japan's education ministry as children who don't go to school for more than 30 days, for reasons unrelated to health or finances. The term has been variously translated as absenteeism, truancy, school phobia or school refusal. Attitudes to futoko have changed over the decades. Until 1992 school refusal - then called tokokyohi, meaning resistance - was considered a type of mental illness. But in 1997 the terminology changed to the more neutral futoko, meaning non-attendance. On 17 October, the government announced that absenteeism among elementary and junior high school students had hit a record high, with 164,528 children absent for 30 days or more during 2018, up from 144,031 in 2017. The free school movement started in Japan in the 1980s, in response to the growing number of futoko. They're alternative schools that operate on principles of freedom and individuality. They're an accepted alternative to compulsory education, along with home-schooling, but won't give children a recognised qualification. The number of students attending free or alternative schools instead of regular schools has shot up over the years, from 7,424 in 1992 to 20,346 in 2017. Dropping out of school can have long-term consequences, and there is a high risk that young people can withdraw from society entirely and shut themselves away in their rooms - a phenomenon known as hikikomori. More worrying still is the number of pupils who take their own lives. In 2018, the number of school suicides was the highest in 30 years, with 332 cases.

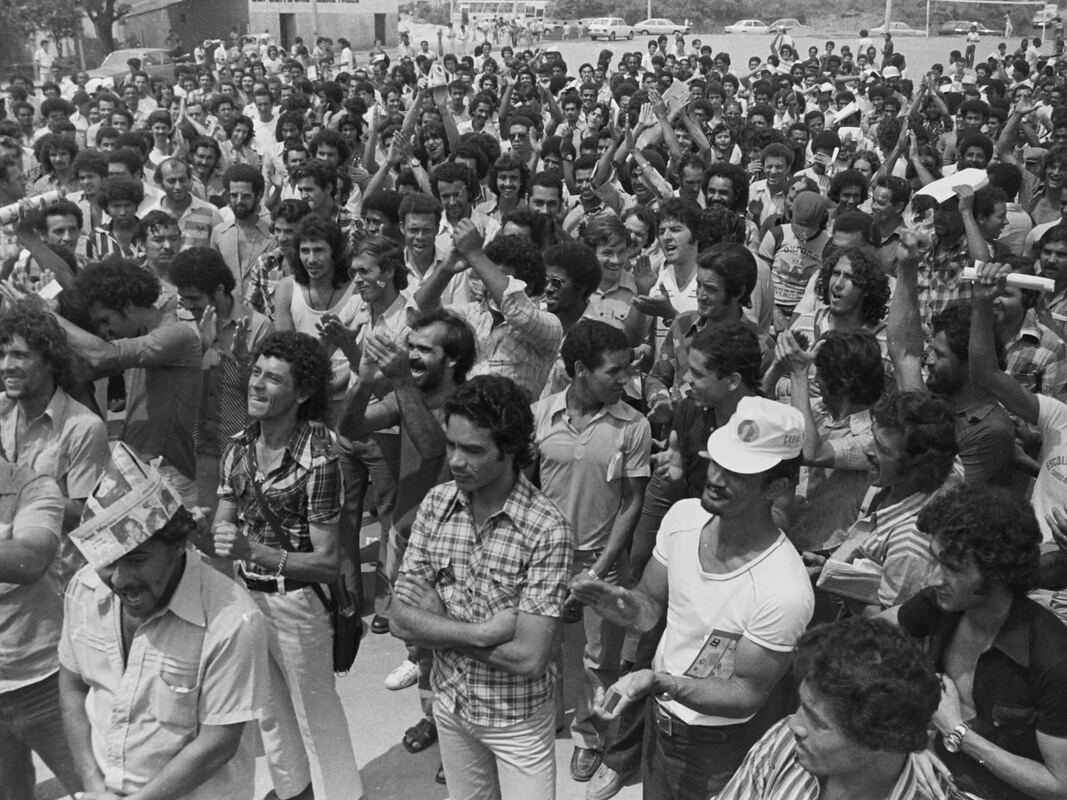

In 2016 the rising number of student suicides led the Japanese government to pass a suicide prevention act with special recommendations for schools. So why are so many children avoiding school in Japan? Family circumstances, personal issues with friends, and bullying are among the main causes, according to a survey by the ministry of education. In general, the dropouts reported that they didn't get along with other students, or sometimes with the teachers. That was also the case for Tomoe Morihashi. "I didn't feel comfortable with many people," says the 12-year-old. "School life was painful." Tomoe suffered from selective mutism, which affected her whenever she was out in public. "I couldn't speak outside my home or away from my family," she says. And she found it hard to obey the rigid set of rules that govern Japanese schools. "Tights must not be coloured, hair must not be dyed, the colour of hair elastics is fixed, and they must not be worn on the wrist," she says. Many schools in Japan control every aspect of their pupils' appearance, forcing pupils to dye their brown hair black, or not allowing pupils to wear tights or coats, even in cold weather. In some cases they even decide on the colour of pupils' underwear. Strict school rules were introduced in the 1970s and 1980s in response to violence and bullying. They relaxed in the 1990s but have become more severe recently. These regulations are known as "black school rules", reflecting a popular term used to describe companies that exploit their workers. Now Tomoe, like Yuta, attends Tamagawa Free School in Tokyo where students don't need to wear a uniform and are free to choose their own activities, according to a plan agreed between the school, parents and pupils. They are encouraged to follow their individual skills and interests. There are rooms with computers for Japanese and maths classes and a library with books and mangas (Japanese comic books). The atmosphere is very informal, like a big family. Students meet in common spaces to chat and play together. "The purpose of this school is to develop people's social skills," says Takashi Yoshikawa, the head of the school. Whether it's through exercising, playing games or studying, the important thing is to learn not to panic when they're in a large group. The school recently moved to a larger space, and about 10 children attend every day. Mr Yoshikawa opened his first free school in 2010, in a three-storey apartment in Tokyo's residential neighbourhood of Fuchu. "I expected students over 15 years old, but actually those who came were only seven or eight years old," he says. "Most were silent with selective mutism, and at school they didn't do anything." Mr Yoshikawa believes that communication problems are at the root of most students' school refusal. His own journey into education was unusual. He quit his job as a "salary man" in a Japanese company in his early 40s, when he decided he wasn't interested in climbing the career ladder. His father was a doctor, and like him, he wanted to serve his community, so he became a social worker and foster father. The experience opened his eyes to the problems children face. He realised how many students suffered because they were poor, or victims of domestic abuse, and how much this affected their performance at school. Part of the challenge pupils face is the big class sizes, says Prof Ryo Uchida, an education expert at Nagoya University. "In classrooms with about 40 students who have to spend a year together, many things can happen," he says. Prof Uchida says comradeship is the key ingredient to surviving life in Japan because the population density is so high - if you don't get along and co-ordinate with others, you won't survive. This not only applies to schools, but also to public transport and other public spaces, all of which are overcrowded. But for many students this need to conform is a problem. They don't feel comfortable in overcrowded classrooms where they have to do everything together with their classmates in a small space. "Feeling uncomfortable in such a situation is normal," says Prof Uchida. What's more, in Japan, children stay in the same class from year to year, so if problems occur, going to school can become painful. "In that sense, the support provided for example by free schools is very meaningful," Prof Uchida says. "In free schools, they care less about the group and they tend to value the thoughts and feelings of each single student." But although free schools are providing an alternative, the problems within the education system itself remain an issue. For Prof Uchida, not developing students' diversity is a violation of their human rights - and many agree. Criticism of "black school rules" and the Japanese school environment is increasing nationwide. In a recent column the Tokyo Shimbun newspaper described them as a violation of human rights and an obstacle to student diversity. In August, the campaign group "Black kosoku o nakuso! Project" [Let's get rid of black school rules!] submitted an online petition to the education ministry signed by more than 60,000 people, asking for an investigation into unreasonable school rules. Osaka Prefecture ordered all of its high schools to review their rules, with about 40% of schools making changes. Prof Uchida says the education ministry now appears to accept absenteeism not as an anomaly, but a trend. He sees this as a tacit admission that futoko children are not the problem but that they are reacting to an education system that is failing to provide a welcoming environment.  (by Janaina Cesar, Pedro Grossi, Alessia Cerantola, Leandro Demori. The Intercept) In October 1978 Fiat Brazil’s workers were on the verge of their first strike. The Italian carmaker’s factory in South America would go on to become its most successful: Today, more Fiats are produced in Brazil than in any country besides Italy, and Fiats are the third most popular car in Brazil. But 40 years ago, as Fiat was growing into its Brazilian operation, turmoil was on the horizon. At the Fiat factory in the Brazilian state of Minas Gerais, workers, fearing repression, had been organizing in secret. The military, which had taken power in a 1964 coup d’état, sometimes violently opposed labor organizing. Yet the Brazilian and Italian Fiat executives couldn’t ignore the palpable energy on the factory floor in Betim, the city where the Fiat plant had opened only two years earlier. Six days before work would eventually come to a halt, Airton Reis de Carvalho, the precinct chief with the local police department, sent a letter to the military. A Fiat worker had been spending hours in front of the police station, trying to locate and free a jailed colleague who was viewed as indispensable to the push for a strike. “There really were Fiat employees who were detained,” Reis explained in his letter. “All of the measures taken by our precinct in this case were in keeping with our agreement with Colonel Joffre, of the Fiat Automotive’s security department.” Reis was referencing Joffre Mario Klein, an army reserve colonel who had joined Fiat’s Brazilian operation in its early days — and who would be at the center of the company’s machinations against its own workers. Under Klein’s careful watch, the Italian carmaker had been spying on Brazilian workers in collaboration with the military dictatorship. Klein’s role in keeping Brazilian workers in check for Fiat, along with a long list of repressive moves by the company, are coming to light after a yearlong investigation by The Intercept Brasil, which tracked down documents from archives in Italy and Brazil and interviewed ex-workers at Fiat, former union leaders, and prosecutors in both countries. The repression of labor at Fiat Brazil came thanks to coordination between the security apparatuses of the Brazilian government and a massive clandestine espionage network operated within the company itself, according to documents at the Minas Gerais public archive. Headquartered in the auto plant and commanded by Klein, Fiat’s internal espionage division employed dozens of civilian and military spies who investigated the lives of workers and helped the abusive dictatorship put agitating workers behind bars. While Fiat’s network of spies operated far beyond the factory walls, closely tracking workers’ activities, the company also invited government repression onto its premises, according to documents from the Office for General Security, a now-defunct division of the Minas Gerais state police. The Brazilian Department of Political and Social Order, a police force known by its Portuguese initials, DOPS, operated freely among Fiat workers. DOPS was infamous for frequently taking the lead in brutal government campaigns of repression against social and political activity, and had employed torture and murder among its tactics since the 1950s. These were the dark forces infiltrating union meetings with the blessing of Fiat Brazil’s own security apparatus. Fiat’s spying operation in Brazil had a parallel back home in Italy. Fiat engaged in the same pattern of espionage in Italy during the “Years of Lead,” a time of Italian political and social turmoil in the that ran from the late 1960s through the late 1980s, according to a second batch of documents from Fiat’s official archives in Turin, Italy, as well as documents from the federal courthouse in Naples, Italy. The Italian spying operation was exposed in the 1970s, when the prosecutor Raffaele Guariniello conducted an investigation and found that Fiat had developed a system of pervasive espionage. A former secret service agent headed up the internal spy ring, and police, judges, and ex-military men were all implicated. The spies compiled hundreds of thousands of files with information about workers’ private lives, including intimate details. The information would prove useful for Fiat in identifying union leaders and ferreting out strike plans. Years after the investigation was complete, the case finally went to court, and some public officials and Fiat executives were convicted. While many of the details have come to public light, however, the history of the Italian spy ring is likely to remain a patchwork: A substantial portion of the evidentiary files from the case have disappeared. In April 2018, in response to an initial inquiry about this story, Fiat Brazil said, “We consulted several sources in the company, but there is really no memory of such events.” In February of this year, Fiat Brazil offered the same comment in response to a detailed inquiry and declined to make company officials available for an interview. Fiat’s Italian headquarters referred The Intercept to the Brazilians’ statement and added, “Regarding the issues concerning Italy, we have no comments to make, because they are well-known things that have been reported in newspapers on many occasions in recent decades and on which books have also been written.”

Qual è il giornalista che non aspira a vincere il Pulitzer, il più importante Premio americano, una specie di Nobel del giornalismo? La domanda è retorica e la risposta è: nessuno.

Lunedì 10 aprile 2017 rimarrà una data storica per IRPI. Sì, perché tre giornalisti della nostra associazione possono dire: “Ci siamo dentro anche noi”. Quel giorno, alla Columbia University di New York l’International Consortium of Investigative Journalists di Washington (ICIJ) si è visto assegnare il Pulitzer per l’inchiesta Panama Papers. E’ l’inchiesta che a partire dall’aprile 2016 ha messo a nudo nomi eccellenti della politica, uomini d’affari, banchieri, personaggi dello star system, protagonisti di scandali legati alla corruzione, narcotrafficanti: tutti legati dal possesso di offshore in 21 paradisi fiscali. Dietro la regia dello studio legale di Panama Mossack Fonseca, autentica “fabbrica” di questo tipo di società, costituite per nascondere patrimoni, grazie al “paperwork” di 50 uffici periferici distribuiti in tutti i continenti... (di Scilla Alecci e Alessia Cerantola per il Fatto Quotidiano)

Li paragonano a centri di scommesse dove il banco vince sempre. Basta un account su cui depositare i soldi e le piattaforme digitali di opzioni binarie sono alla portata di tutti. I siti attraggono esperti e principianti che, con transazioni virtuali della durata di pochi secondi, puntano anche decine di euro sull’andamento di prodotti finanziari come petrolio o valute. A seconda che il prezzo salga o scenda, l’utente vince o perde una somma prestabilita, proprio come accade con il gioco d’azzardo. Ma, attenzione, si legge su alcuni siti, “gli investitori potrebbero perdere tutto”. E se a gestire la piattaforma sono aziende internazionali che possono sfuggire a controlli preventivi il rischio aumenta. Dal 2014, 24option è un marchio di proprietà della Rodeler, una società cipriota specializzata in consulenza e investimenti finanziari, ed è partner commerciale della Juventus. |

Archives

August 2023

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed